Large Format Color Printers as an Aid in Archaeological Research for Recording Ancient Maya Pottery

|

The study of style and iconography of several related regional ceramic workshops of the Tikal Peten area and the Motagua River area of Highland Guatemala can be aided by the newest technology of large format inkjet printers.

The study of iconography is not restricted to limiting itself to the traditional corpus of pots which are published in the official site reports for Holmul, Uaxactun, Tikal, etc. The study of Maya iconography has been open to the analysis of all Maya pots which have been photographed. The result is that the corpus for iconographers is perhaps ten times that larger than the corpus used by ceramicists.

An example of the results available from the larger corpus is the Motagua-Peten regional sharing of a carved style. The pots themselves are well documented for Tikal: one example is in the burial of Ruler A. Twelve pots of the same style were found in a royal burial of a close relative of Ruler A in Burial 196. Yet when these pots were published in the official Tikal ceramic report, no mention was made that this ceramic style is related to one of the dominant carved styles of the Motagua River area.

Over the last twenty years, as I have sought out Maya pots to photograph, it has been possible to record dozens and dozens of pots which are related to the Tikal style and/or to the Motagua style. I show such an example here.

One portion of the Motagua corpus was made in the Motagua area of Highland Guatemala. The Museo Popol Vuh has perhaps five to ten pots of this regional style. The pots are characterized by elongated hieroglyphs which are clearly not the kind filled with phonetic information so beloved by iconographers (in other words, the Motagua glyphs are crudely rendered). God N and Long Snouted deities are the favored motifs for the panels. The flat areas (the frames for the decoration) tend to be stuccoed with pink, blue, green, or red paint.

A second style has hieroglyphs rendered in a more Classical style though the Primary Standard Sequence is seldom found, even on examples from the Tikal royal burials. It is a challenge to ascertain which pots of these styles were made in the Motagua and exported to the Peten, and which were made in the Central Peten. An alternative explanation is that the origin of the overall style was the Central Peten and that the wealth of the jade miners and merchants of the Motagua used their jade wealth to import both actual pots from the Peten as well as to finance local Motagua workshops to reproduce pseudo-Peten styles locally.

Similar situations exist for Chama pots: more Chama pots have been found in the Motagua drainage than have been found in the entire Chama area.

The same for Escuintla pots: as many pots in Late Classic Costa Sur styles have been found in the Motagua drainage as have been found in the considerably larger Depto. de Escuintla. Indeed when I find a pot which I interpret as being in a late Escuintla style, Dr Guillermo Mata has often documented that the vase in fact came from a burial directly along the Motagua River.

Overall this makes the Motagua area the most international port of pre-Columbian Guatmala. More exotic "foreign" pots have been found in the miserable desert area of the Middle Motagua than in the great regional capitals of Tikal or Calakmul.

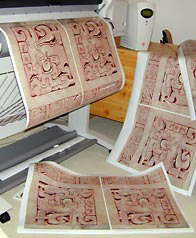

The images pictured here are part of a long range evaluation of digital imaging equipment. The enlargements shown here are from direct digital rollout photographs from a Better Light large format digital camera (pictured and described on www.digital-photography.org). The prints are at 600 dpi with an Hewlett-Packard DesignJet model 2800 CP, a wide format color inkjet printer.

The image is prepared on a Macintosh computer in Adobe Photoshop and Adobe PageMaker and then sent to a hardware RIP, a raster image processor (in effect a separate computer which acts as a print server). The RIP is pictured here (the mascot, an anthropomorphic sheep sits atop the RIP); to the left of the RIP is the control panel of the wide format printer. This is a portion of the equipment in the F.L.A.A.R. Photo Archive Digital Imaging Technology Center. This digital imaging center is in Essen, Germany, coordinated with the Guatemalan branch of the same F.L.A.A.R. Photo Archive at the Universidad Francisco Marroquin, Museo Popol Vuh, Guatemala. The Guatemalan research center is pictured on www.wide-format-printers.org and www.large-format-printers.org.

Each image is one panel from a typical two-panel carved pot. I have cropped the one panel for a test of unsharp masking, a digital form of sharpening a digital image (scanning softens an image, the only major downside of digital photography or scanning of traditional film).

In this test I have taken one panel and sharpened that panel with one out of eight different test strengths as a comparison. I have fit two samples per 36 inch width of the roll of photo paper (so each panel has been enlarged to about 17 inches in width). Such an enlargement is not feasible with most rollouts taken with film since most film-based rollout cameras are not in perfect synchronization with the rotational speed of the pot. The out-of-synchronization results in a lack of focus which is even worse than the soft focus of digital imaging. The digital image is in perfect focus, it is just not with sharp edges.

The test shows that an unsharp masking of 150 1 10 is appropriate for a vase of these surface characteristics and for this percentage of enlargement. Sharpening digital photographs of pottery is difficult because too much sharpening makes the grains of temper and other particles stand out from the background, creating an unnatural sandy surface.

Most Recently Updated: June 2009